Key Messages

Supporting people to achieve their “Best Weight”, NOT “Ideal Weight”

Health professionals have been focused on the concept of ‘Ideal Weight’ for too long.

This concept arises from so-called ‘normal weight’ range in BMI categories. BMI is a useful concept in monitoring population health, but it is only one part of assessing a patient’s overall health and well-being. Because weight is strongly determined by genetic predisposition, and biological and psychological factors acquired during growth and development, in combination with living in our current obesogenic environment, achieving a so-called ‘normal’ weight can be extremely difficult for people living with obesity.

If we think about our goals when caring for people with chronic diseases such as congestive heart failure or COPD, we understand that we are not able to ‘cure’ these diseases. We are not treating them with a goal of achieving a ‘normal’ heart or lungs. We know that chronic disease management means supporting people to live well with the disease they are living with, using treatments that reduce symptoms and hospital admissions, and prevent or delay progression of the disease. When we approach complex and severe obesity with the same chronic disease management approach, we can understand that we are not aiming for a ‘normal’ weight or BMI. We are aiming to help PwO achieve and maintain a healthier weight and preventing or managing complications of the disease.

Focusing on achieving ‘best weight’ can be a more helpful concept to discuss with patients. A person’s best weight is the weight they can maintain, while living the healthiest and happiest life that is sustainable and enjoyable for them.

A recent International Obesity Collaborative Consensus Statement summarises the importance of obesity care versus weight loss.

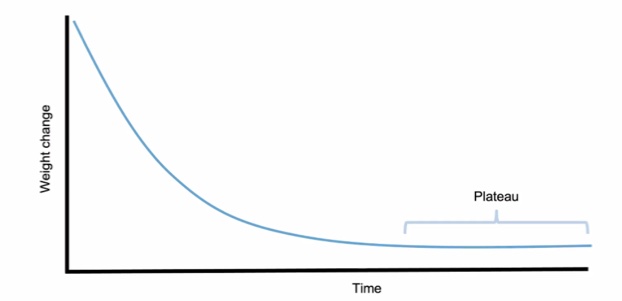

The Weight Loss Curve

This graph describes the outcome of all weight loss interventions. Weight loss is not linear. HCPs and patients need to understand that the human body is hard-wired to resist weight loss, so regardless of dietary, pharmacological or surgical interventions, they will all follow a similar pattern of initial weight loss and then a weight plateau.

If a patient does not understand or expect this, there will be understandable frustration that weight is not reducing, in spite of continuing with the same healthy behaviours that were initially associated with more rapid weight loss. Frustration and feelings of failure can lead to reduced confidence and self-efficacy.

In appropriate situations, this may be the time to discuss escalation of treatment, with medication or surgical intervention. But in all cases HCPs should be supporting a focus on health gains achieved, and weight maintenance, rather than contributing to an expectation of a continued reducing number on the weighing scales.

You can read more below on the science of energy balance and metabolic adaptation to weight loss.

Energy balance and homeostasis – recognising the complexity of weight loss and gain

Energy balance is controlled by a complex homeostatic biological system, with communication between many organ systems and the hypothalamus in the brain. Homeostasis describes the self-regulation of many complex processes in the human body, where equilibrium or balance is maintained on an ongoing basis, without conscious input, without us being aware of it. Examples include temperature regulation, blood pH, breathing, blood pressure, fluid balance, sodium, potassium and calcium levels.

Many diseases are the result of homeostatic dysfunction, either because of an inherited defect or an acquired disease.

The idea of homeostasis is important if we are to have a holistic approach to weight management. Each person has a particular weight or body fat mass ‘set point’, initially determined by genetics and epigenetics and then modified by developmental and environmental factors. Factors such as chemical and nutrient content of food, ‘unhealthy’ muscle, sleep restriction, circadian misalignment, chronic stress and pain, and medications promoting weight gain, can push the set point higher.

The body will defend this ‘set point’, so if weight is lost through dietary modification, homeostatic regulation will aim to regain the weight, through hormonal changes that increase hunger and reduce satiety (fullness), and reduction in metabolic rate, so the body is now more fuel efficient.

In addition to reduced calorie intake, we need to identify and address these other factors that can contribute to a higher weight set point, if we can. Or at least acknowledge and discuss their influence with patients, so they will understand why losing weight is so challenging. For example, they have made some dietary changes and are now following a healthy eating pattern, but they are working night shifts, and/or they have chronic severe back pain, so this may mean they reach a weight plateau sooner than expected.

And we need to understand that in many cases, particularly at higher weights, with more complex obesity, we will often need to consider medications and bariatric surgery, in order to support substantial and sustained weight loss.

The GateKeeper, the GoGetter and the Sleepy Executive is a helpful 9 minute video that explains the complex role of the brain in weight management.

What is the role of genetics?

Genetics have a huge influence on energy regulation. In fact, genetic predisposition is often the factor with the biggest contribution to obesity risk, with 70-80% of variability in body weight attributed to genetic variation, in twin, adoption and family studies.

Acceptance of the strong genetic influence in obesity could be perceived as discouraging to people struggling to lose weight. But increased awareness of genetic influences will not discourage individuals from trying to live a healthier lifestyle.

Instead, people are usually relieved to hear that they are not the lazy, weak-willed person they thought they were. In the context of other diseases, patients often express relief when they have been unwell for a long time and are given a diagnosis that gives an explanation for their symptoms. They are not relieved to hear they have a disease, but thankful to finally have an explanation, and to be looked after by a clinician who understands the disease, and wants to help and support them to live well with the disease.

Biology influence on behaviour

Biological impulses can influence what we perceive as behaviours. For example, dietary-induced weight loss is associated with an increase in the hunger hormone ghrelin, and reduction of several satiety (fullness) hormones, including Amylin and Peptide YY. This causes increased hunger and food cravings, and a difficulty feeling satisfied, leading to larger portion sizes or eating more frequently. This often results in weight regain, not because of greediness or a lack of willpower, but because of powerful homeostatic biology.

Clinicians don’t need to fully understand these complex biological systems, but we do need to understand that a complex biology exists, and this is influencing feelings of hunger and fullness, how soon we feel hungry again, if we feel full at all and for how long. We need to understand that our subjective sense of fullness with a particular portion size is not the same as anyone else. It won’t even be the same for us on different days, depending on if we’ve recently lost weight, or if we are in pain, stressed, or tired.

Obesity Definition

Obesity is defined by excess or dysfunctional adiposity and associated health impairment.

This definition does not include weight or BMI, as the focus is on health impairment rather than a number on a weighing scales. This definition refers to health in the broadest sense, including metabolic, physical, functional, psychological and social health. If someone has a higher body weight, but does not have any health impairments, they do not have obesity. They may have an increased risk of health impairment developing over time and offering them screening and supporting a healthy lifestyle is important, but they do not have disease and do not necessarily need treatment. Similarly, a person with BMI 29kg/m2, and multiple health impairments, including type 2 diabetes, sleep apnoea and PCOS, does have obesity, and they need appropriate treatment.

Chronic Disease Model of Care

When governments and health systems and public health campaigns and health care professionals start to truly recognise and treat obesity as a chronic disease, the way we care for people with obesity will be the same as other chronic disease models of care. We use chronic disease principles when managing diseases such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, COPD, and Heart Failure.

As an example, let us consider the management of type 2 diabetes – if patients attending a diabetes clinic were just given advice to eat less and do more exercise, many patients would have very poor diabetes outcomes. That approach would only work for a minority of patients with type 2 diabetes. The standard of diabetes care includes multi-disciplinary team care, with regular review and a long-term shared care approach between the community and hospital as needed, in addition to a variety of reimbursed medication options that support lifestyle measures.

People with obesity deserve a standard of care in line with all other chronic diseases.

Effective and appropriate chronic disease management requires a published Model of Care, and this was finally delivered for obesity care, with the launch of the National Clinical Programme for Obesity Model of Care in 2020.

Take home message for health professionals

We need to keep reminding ourselves that successful outcomes for patients living with obesity are not exclusively measured through the degree of weight loss achieved, or the results of blood tests or blood pressure measurements.

We can also be successful if we are having unbiased, evidence-based and collaborative consultations, where the other person leaves feeling that you listened, that you understood and that you did not judge them.

As Maya Angelou said: “People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”